From a chronological point of view, the few manuscript pages containing Ion Monoran’s first poems, together with the thirty-odd pages of his army diary, represent the first documents in the Ion Monoran Collection. The years that mark the beginnings of the collection are 1972–1974. In time to these first manuscripts were added some hundreds of pages of poems. All the elements that make up this collection are privately owned and they are currently kept in the Monoran family home.

Ion Monoran’s army diary documents a delicate and very tense period in his life: his military service, in very difficult conditions, in the years 1974 and 1975, in a unit to which those considered hostile to the communist regime were sent. This posting – to the unit serving a petrochemical plant in the south of Romania – was due to the fact that, while at high school, Iona Monoran, together with some classmates, had tried to flee the country secretly, resulting in his expulsion from school.

Through the 1980s, the collection grew steadily, with the result that, together with his objects for personal use and the typewriter he bought in 1984, it makes up a unitary whole. It is worth emphasising that the typewriter was an object with a special regime under Romanian communism, as the authorities considered it an instrument with subversive potential. According to the legislation of the time, anyone who possessed a typewriter was required at the beginning of each year to provide the Militia with a sample of text typed on it. Like human fingerprints, the letters typed on a typewriter have distinguishing characteristics. The possibility of distributing manifestos or samizdat texts in communist Romania was thus drastically reduced, as the origin of any such clandestine text could easily be established if it was produced by multiplication using a typewriter.

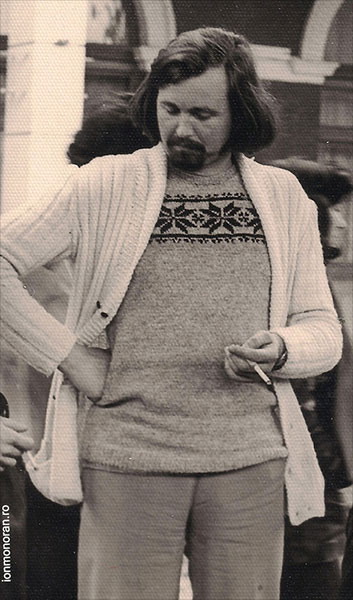

The most numerous category of documents kept in this collection is that of manuscripts containing poems. Many of these have a pronoucned social character and are markedly critical of the communist regime. Out of the hundreds of poems Ion Monoran composed, very few were published before 1989, and indeed relatively few before his premature death in 1993. Due to his late, indeed posthumous volume debut, which took place only in 1994, he remained a marginal figure in Romanian literature. If he had had a normal career, Ruxandra Cesereanu observes in an article in the magazine Steaua (7–8/1994), Monoran’s poetry should have been a reference point for his generation, which is known in Romanian literature as the eighties generation, from the decade of their debut. Likewise, the writer Marcel Tolcea, a fellow member of that generation, writes in a review in the magazine Orizont (3/1994) that Monoran’s poems represented “a totemic model for their generation.” The great majority of these poems are written in a “biographical” register, as they are characterised by the writer Mircea Cărtărescu, the most well-known representative of the eighties generation, and the only one also to have an international career (Cărtărescu 1999, 156). They foreground a free spirit, as is shown by the following quotation: “I am a stormy boy, who knows how to write riskily for the official canon of the communist period, but I wager / that no editor would dare / to publish a text like this in magazines / still less the ideologists / with whom one of these days I’m going to thrash things out anyway…” (Monoran 1994, 32). This extract illustrates the fact that, in choosing to write as freely as possible, Monoran chose consciously to remain practically unpublished until the fall of communism. Before 1989, only a few of his poems appeared in magazines. All Ion Monoran’s books appeared posthumously: Locus Periucundus (1994); Ca un vagabond într-o flanelă roșie (Like a tramp in a red sweater, 1996); Eu însumi (I myself, 2009).

Many of those who have commented on the poems of Ion Monoran have mentioned a certain predisposition towards insubordination, a “bellicose” impulse. “His taste for insurgency was to find its fulfilment during the revolution, when Ion Monoran was among those at the forefront: it was he who stopped the trams in front of the house of Pastor László Tőkés and urged people to rise up against the dictatorship” (Vighi 2005, 524).

After 1989, the Ion Monoran Collection was supplemented with many items that had appeared in the press. On the one hand, there were various texts – poems or articles on social and political themes – that Ion Monoran had written before 1989, but that had remained “works for the drawer” until the revolution. On the other, there were numerous references to the cultural and social activity of Ion Monoran, published in abundance in the press of the first years after the fall of Romanian communism.

The articles published by Ion Monoran after 1989, most of which are in the private collection of his family, document this “taste for insurgency” and for justice from another perspective. Although they were not created under communism, they mostly refer to the way in which the communist past ought to be treated, to the necessity of de-communisation, and to the initiation of transitional justice.

Monoran was a founder member of the newspaper Timișoara, a regional publication that is representative for the liberation from communism in the first years after December 1989. He was also a founder member of the Timişoara Society, one of the most important civil society groups in the post-1989 period. Moreover, it was in Ion Monoran’s apartment that many paragraphs of the so-called “Timişoara Proclamation” were written, the first public document after 1989, in which representatives of civil society called on the post-communist authorities to initiate the process of eliminating from public life former members of the Communist Party leadership and former employees of the Securitate.