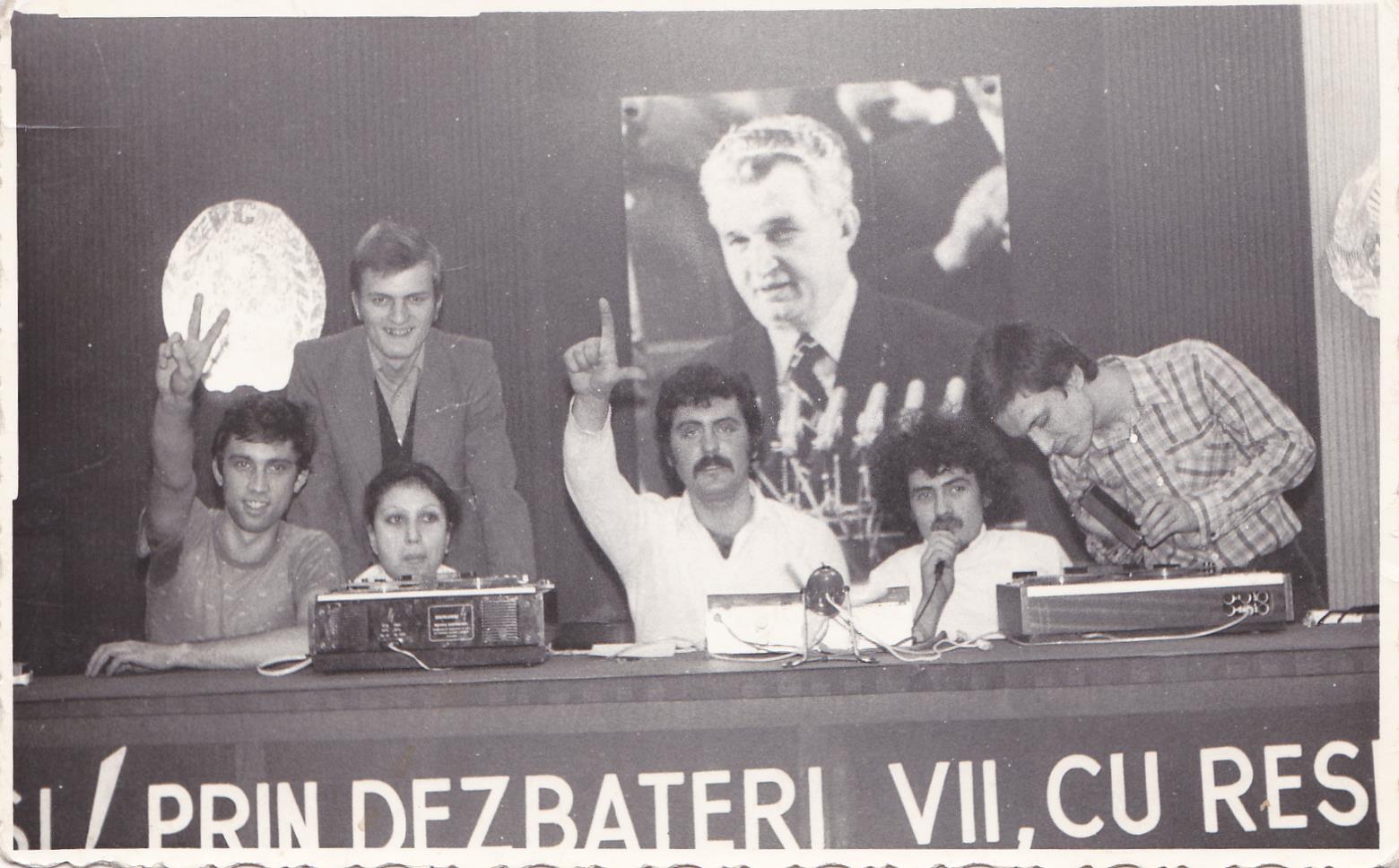

Before 1989, collecting concert posters was not a forbidden activity, or even a tolerated one. Rather it was a marginal activity that went on outside the official circuit of performances. Under communism there were no official channels by which concert posters could be obtained, for example by buying them in bookshops or second-hand bookshops, because the posters were printed for a purely utilitarian purpose, to be displayed in specially arranged places. Concert halls used them to announce an event and then threw them away. Given that these halls had no affiliated shops, only ticket desks, they had no way of commercializing them. Consequently the collection of concert posters was an activity that could not be maintained without the existence of the black market and of an informal network of enthusiasts for music that was considered alternative in relation to the so-called “Theses of July 1971.” In July 1971, the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party, Nicolae Ceaușescu, condemned servility towards Western cultural models, or – as he put it - any “kowtowing before all that is foreign, and especially before what is produced in the West” (Ceaușescu 1971, 48–49). Ceaușescu’s speech remained an important reference point for communism in Romania because its long-term effect was the country’s cultural isolation in relation to the Western sources of inspiration that had driven its development since the nineteenth century (C. Petrescu 2008). Among the musical genres considered alternative, some were, however, permitted in the public space. As the concert posters of the time confirm, musical genres such as jazz, rock, and folk made up part of this category that was tolerated by the communist regime, probably in order to offer young people a setting in which they could give expression to the nonconformism characteristic of their age, while at the same time being kept under control. It is interesting to note that, out of these three genres, it was folk that lent itself the most to being preserved in form while fundamentally modified in essence. From an anti-system and anti-war music of the 1968 generation, it was autochthonised in the Romanian context into the genre of ethno-folk, finally becoming a music of “revolutionary youth,” which from the mid-1970s was hitched onto the communist regime’s propaganda apparatus through the so-called Cenaclu Flacăra (“Flame Cenacle”)(Ionescu 2016). Unfortunately many of the young people of the time did not grasp this gradual change and continued to perceive folk as a music that was addressed to their generation and alternative in relation to the music listened to by their parents’ generation. While some young people were incapable of discerning how apparently non-conformist music was in reality unofficially supported by the regime, there were plenty whose passion for music led them towards nonconformism, towards a distancing from all that was officially promoted, and even towards a critical attitude towards the communist regime. Collecting posters for jazz, folk, and rock concerts was a way of opting for all that was going on in the grey zone of tolerated nonconformist activities. Such collections had at that time, as they have today, no real artistic value, for the concert bills were rather dull, included mostly informative texts, and required no particular skills from the individuals who drew them up. In fact, the authors of these bills remained unknown. Before 1989, under a regime that strictly controlled and heavily restricted the circulation of information, the main value of such items was primarily informative. Today these concert bills have great historic value in the reconstruction of the alternative musical subcultures under the communist regime in Romania.

It was his passion for music that triggered Mihai Manea’s passion for collecting posters from and about concerts of rock, folk, and jazz bands and performers. He recalls what propelled him to start his collection: “The teacher I had in primary school had an extraordinary influence on me, including in a musical sense. She had a habit – quite out of the ordinary in that period, at a time when things were very rigid in the education system – of coming with a record player and playing music during classes. She played us various records; she talked to us about music – of course music was one of her great passions too. She also took us to the Opera; I saw Ophelia, I saw the Nutcracker in that period. I listened at school – and I was very lucky from that point of view, as I would realize later – to dozens of records, of classical music (a great many), rock, folk. Well, my teacher’s insistence sparked something in me, something that, perhaps in a subtle way but insistently, was to mark my life and my professional trajectory. Because later on, a great many things, in my life, would be connected to music… In this way I caught the taste of music.” So Mihai Manea concludes his recollection of the extraordinary impact of these music lessons in primary school, delivered in rather unusual conditions in relation to the rules of operation of the education system during the communist regime.

The next step was for him to develop this passion on his own, which then led him to the idea of collecting concert posters: “And after that, I began to go on my own; I began to seek out music, to want to listen to as much and as varied music as possible. I began to go to concerts on my own. And it was then that the first concert posters appeared in my life and in my room.” In other words, the young Mihai Manea’s passion for music developed in such a way that the music itself became only part of the ritual associated with a concert. From a mere spectator, he became a committed spectator, who wanted to find out more about the people appearing on stage, so he began to go backstage, which opened up access to a new universe for him and made him want to preserve the memory of each musical event that he had participated in. “Timidly at first, but later as if it was something perfectly normal, I dared to go backstage at concerts – at least to the extent that I succeeded in doing so and that I was allowed. In fact in trying to get backstage at concerts, I wanted to get as close as possible to all that the concert was about, I wanted to know how music was made beyond what I was about to see or had just seen on the stage. And so I began to get concert posters: asking, basically asking if I could have a poster for this or that concert. And I started to gather them: one or two posters from one concert, a poster or two from another. I took them and, at first, I put them on my wall.”

Regarding the way in which his collection was born and developed, Mihai Manea recalls that it all began without any clear plan to build up an archive, but this grew imperceptibly until it awakened the collecting passion in him. The first posters entered his collection in 1969–1970, when he was a teenager at middle-school, aged 14–15. “That’s when this madness began – just gathering concert posters, as many as possible.” In time, the number of these posters grew, with the result that their presence on the walls of the teenage Mihai Manea’s room became seasonal. The accumulation of posters beyond the exhibition space provided by the walls of his own room created the premises for systematic collection, for ordering the collection and organizing storage space. “And these posters began to gather because, in fact, after new posters came, I didn’t throw away the ones that I unstuck from the wall. I put them in boxes, nicely arranged, and so they began to keep gathering.” The posters gathered in Mihai Manea’s collection each year went into double figures. “Of course from year to year the number varied, either because it happened that one year there were fewer concerts whose posters I had access to, or because some concerts were repeated,” explains Mihai Manea. Reflecting further on the way in which his collection was born imperceptibly, he adds: “After a while, they started to look as if they were a collection, but I didn’t start gathering them with the idea that I might have such an archive. I simply started gathering them and their number grew and grew. They became a collection of their own accord, I would say, a symbolic archive of what was, partially, the musical dimension of those times.”

One of the purposes for which these posters started to gather in Mihai Manea’s home was strictly informative. Given that in communist Romania there were no databases or encyclopaedias of music groups, the posters were a free source of information in those times. For example, the composition of these groups was a type of information that mostly circulated informally, being formally presented only on the sleeves of their vinyl discs. “Especially on the older posters, on the ones that date from the start of my activity as a poster-gatherer, and particularly on the posters for rock groups, there was other information: sometimes about the composition of the group at that time. Now, for those years, when information was quite hard to get, what was printed there, on those concert posters, meant something. You knew who the people were who played rock; you were, as they say, up-to-date. On top of that, just as others – but not in Romania – had glossy photographs of bands on their walls, I had posters. It was, at first, a youthful passion, the passion of a teenager who was crazy about music.” In the 1970s and 1980s, Mihai Manea points out, there were quite a lot of music concerts in Romania. He points to 1977 as being a turning point in the history of concerts – especially those of rock and jazz. On average, up until 1977, approximately twenty concert posters entered Mihai Manea’s collection every year. From then until 1989, the restrictions and formulas of control became more drastic, which meant that concerts were also reduced in number, and the number of posters entering his collection annually dropped correspondingly: “Maybe ten, maybe fifteen per year, at the most,” says Mihai Manea.

The concert posters from the communist period in the possession of Mihai Manea were of varied provenance. Most of them, he explains, were obtained directly from ticket desks or from the producers and organizers of concerts: “They weren’t sold at the ticket desk of course. But in time some habits and connections were built up and I got to the point where I could just go up and ask for spares. And usually I got them.” Another source that Mihai Manea resorted to was the posterposters: “I cultivated some connections here too, and it often happened that the people who stuck posters on the walls specially arranged for the purpose would find one or two for me.” Sometimes, he adds, “I would take them straight from the panels; some of them weren’t very well fixed, and if you know what to do and had the patience, you could unstick the odd poster without much damage. There was, I remember, a solution made from flour, water, and a little caustic soda, and if you got there when they were freshly posted you could get them down from the wall relatively quickly.” Some of the concert posters were quite simply bought, on what might nowadays be called the black market of the alternative economy. “You bought concert posters there, but not only concert posters,” remarks Mihai Manea. And he adds: “They didn’t cost much; it was just a matter of a few lei, but the goods were quite rare, because not many posters were printed, and those who printed them were generally very carefully watched. But from those places where I bought or exchanged concert posters, I got a lot of other things: discs, especially vinyl, sometimes cassettes.”

The story of the places where those who collected or dealt in objects such as discs or (more rarely) concert posters met to exchange or sell is fascinating in itself. As Mihai Manea tells it: “It was like a sort of stock exchange, but a primitive one, of course. Because in fact there was no organized space; we met on the street. Most often we met in front of the Muzica shop in Bucharest, on the pavement that lay just a few dozen metres from the façade of the building of the Central Committee of the Romanian Communist Party. There was no dissidence about it: all we wanted was to have music, as much music as possible and as up-to-date, as new as possible. The Militia would sometimes come down on us and they would break up the group that sometimes gathered and could be quite big. And then we would move down a street or two, behind the Kreţulescu Church or into the area in front of the Palace Hall.” This unusual “ritual” took place, as a rule, weekly: every Thursday. “Ten, twenty, sometimes even thirty of us would come, the majority young; we knew one another. We had discs under our arms or in shopping bags; we sold them or exchanged them; we bought others. Discs, concert posters, cassettes. We exchanged, bought, and sold music; but we also talked about music. And then we moved on, home or to clubs or to the Radio. Because among us there were stars of the time, people with a lot of exposure on the radio. Florian Pittiş, for example; a man who did a lot for music of quality even before 1989. We talked a lot about music there; I got a lot of information, and I gave a lot of information in my turn. It was a sort of talk-show in the street, a sort of live debates.”

For a music enthusiast such as Mihai Manea had become, his collection of posters from concerts was an increasingly significant source of information for his ongoing activity as an amateur, and later as a professional. With the help of the posters, but also with the help of music articles in the newspapers and magazines of the time, Mihai Manea could date various musical events and could navigate more and more easily in the world of young people with a passion for music. This information became essential after he finished high-school, when a large part of his professional activity was closely connected with various musical styles and genres. He began as a volunteer, a “man behind the concerts,” to get involved in solving problems particularly of a technical nature, and later even in the organization of musical shows. From 1978, Mihai Manea became a coordinator of discotheque activities for young people, and from 1982 he also played a role on stage, as soloist in the rock band Barock Group, which he himself had founded. Thus Mihai Manea found several outlets for the passion for music triggered by his primary teacher, continued and consolidated by attending concerts, and then by collecting concert posters. “The eighty to a hundred concert posters that I still have today are, as I was saying, also about me, about my passion,” he emphasizes.

Finally, Mihai Manea mentions and insists on a nuance in connection both with the concert posters and with the attitude of the authorities towards music, and especially towards those musical varieties that were not necessarily “aligned” with the operational logic of the communist regime – especially rock music, but also jazz. He says that the big shows, those for which he still has a good few dozen posters, were all approved by the regime. “You had to go to them. And they had concert posters. Even if the music there wasn’t completely “in line,” it was permitted. It was also a way of keeping under control a phenomenon that was connected, without a doubt, to a certain youthful revolt.” For other performances, however, there were no posters, explains Mihai Manea. “Those were the ones that took place in clubs. Such as was the case of the numerous concerts that took place in Club A, which was famous in Bucharest in the communist period. They had no posters. And at the entrance there were always men from the Militia, very attentive. I knew that in clubs great artists were performing who were perhaps even problematic for communism, but I didn’t find out in a public way, from announcements. I found out about them by word of mouth, person to person. Well, if there had been concert posters for that sort of thing, they would probably have been at least a precious as that ones that I have now. Because at those concerts, things were said more directly, more up front.” Consequently, the officially tolerated concerts took place in concert halls, they had posters, and thus their memory was preserved through collections like Mihai Manea’s. The unofficially tolerated concerts took place in clubs, left no material trace because they had no posters, but their memory was preserved by some of the participants and transmitted by way of interviews and publications to future generations (Doru Ionescu 2011).