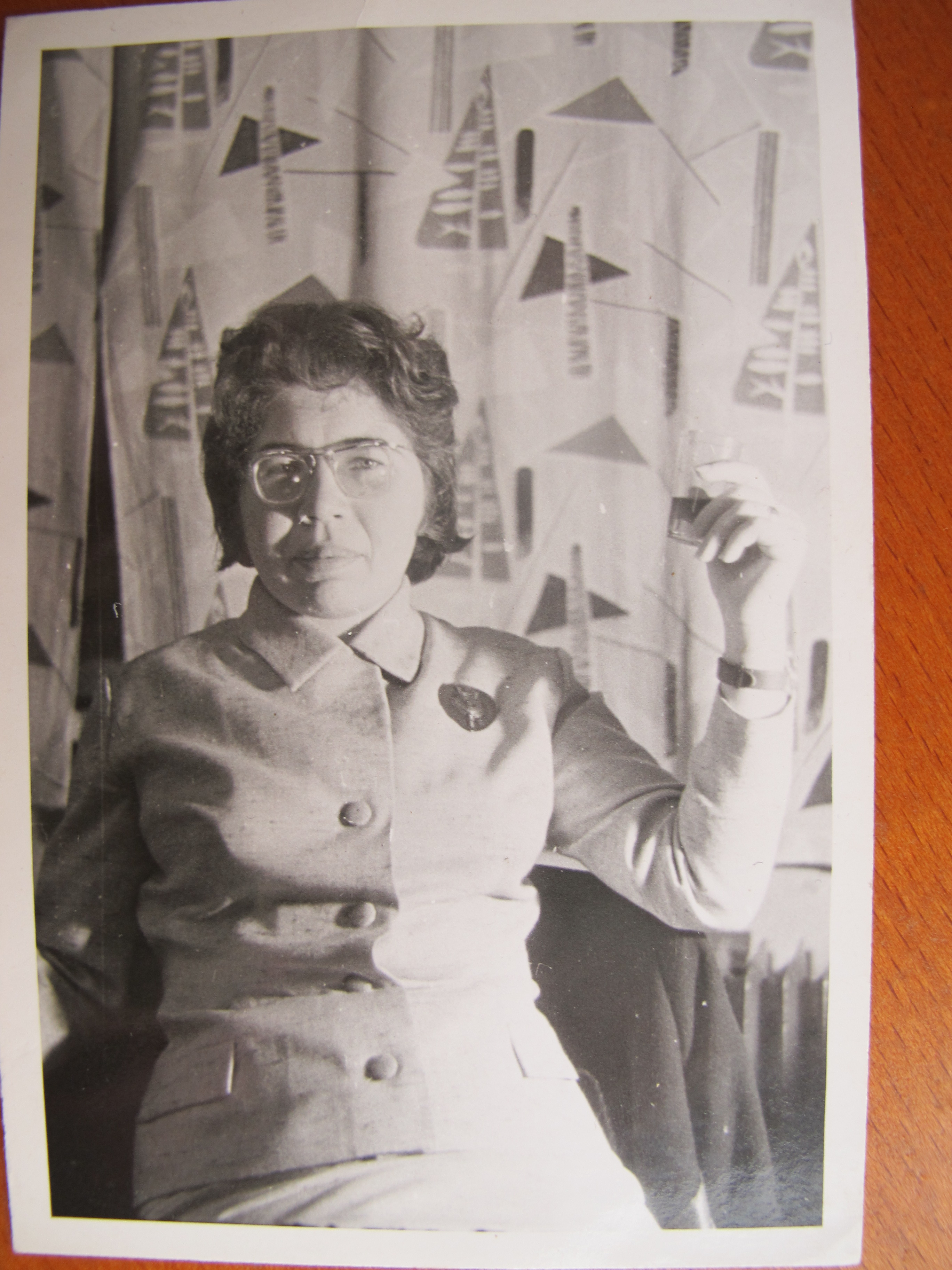

Born in Shumen in 1934, Sevdalina Panayotova spent her childhood and youth in Sofia, where she graduated from the University of Sofia in Bulgarian philology in 1956. During her studies she became close to Petar Peev and Georgi Konstantinov, who in 1953 attempted to destroy the monument of Stalin in Sofia, but were arrested. Stalin's death on 5 March 1953, which coincided with the planned destruction of the monument, spared them a death sentence. They were sentenced to 20 years in prison in a forced labor camp in Belene on Persin Island. As their follower, Sevdalina was also declared an "enemy of the people", and thus was a subject of observation by State Security throughout her life.

During her student years, 1953-1956 the Sofia home of her parents, Petar and Vena Baychevi, became a center for a large circle of young people who gathered to debated, create, and argue. Another “alternative” place was the so-called "doghouse" on 23 Ivan Rilski street, where Assen Ignatov (a philosophy student, close friend of Sevdalina from Shumen, considered a leading contemporary philosopher; emigrated 1973), Konstantin Pavlov (poet), Mihail Berberov (poet), Uzuna (Dimitar Uzunski, long-time editor of the Shumenska Zarya newspaper, poet, fiction writer), Nella Dancheva (poet, long-time journalist in Shumen), Petko "the mayor", Manol "the dog", and others met and critically discussed the reality of socialism and undertook alternative political work. Together with some of her colleagues, Sevdalina participated in preparing an anti-communist rally, which was to take place on the evening of 7 November 1956, as a show of solidarity with the Hungarian revolution. However, the organizers were arrested, including Sevdalina Panayotova (then with her father’s family name, Baycheva), and the rally fell apart.

From 1959 until her death, Sevdalina Panayotova lived and taught in Chepelare (only living in Sofia during the period 1969 to 1974 with her husband Panayot Panayotov and her two daughters Teodora and Boryana). In 1972, Sevdalina Panayotova led a group of dissident intellectuals such as Rozalia Likova, a professor at the Kliment Ohridski Sofia University, Hristo Sabev (later known as Christopher Sabev), her old friends Petar Peev and Georgi Konstantinov, former students from Chepelare, then current students in Sofia such as Lika and Stefan Marev, Zlatko Kalaydzhiev, Maria Stoeva, and others. They gathered (most often) in the home of Sevdalina’s parents. Apart from political discussions, they read and discussed forbidden literature (documented in their State Security files by day, hour, and minute).

After Georgi Konstantinov, an anarchist who had laid a bomb at the Stalin statue, fled to the West in July 1973, Peter Peev and Sevdalina Panayotova were declared "anarchoterrorists" and accomplices of Georgi Konstantinov, and were accused of belonging to an illegal terrorist organization. In September 1973, Petar Peev was sent to the forced labor camp in Belene on Persin Island for three years, and in November Sevdalina was detained for 40 days at the Investigation Department of State Security at Razvigor Street No. 1 in Sofia. At that time, she was 39 years old, her elder daughter, Teodora, was 13, and her younger daughter, Boryana, 7. The rest of the group were also arrested and interrogated. In Emigrant memories, volume 1, Georgi Konstantinov, through the archives of State Security, proves that the repressive structure of State Security aimed to "collect materials" with the goal of starting a legal process against Georgi Konstantinov, Petar Peev, and Sevdalina Panayotova as organizers of an illegal movement of anarchoterrorists to overthrow communist rule. One of their "successful actions" – in the view of State Security – was the illegal emigration of Georgi Konstantinov. State Security assumed that they associated with Western counterparts. For the collection of "evidence", the State Security used numerous means: eavesdropping, threats, extortion, recruitment, violence (as evidenced by the thousands of pages stored in the State Security archives). Georgi Konstantinov himself says in his book that Peter and Sevdalina were never anarchists or terrorists, and even writes about Sevdalina's "literary circle" in a condescending manner. The investigation of the anarchoterrorists was terminated in the spring of 1974. After her release, in order to avoid exile Sevdalina returned to Chepelare, where she taught, organized a school theater, and wrote for the rest of her life. She turned speech into the main means of her opposition to the socialist regime. The word in all its forms, in writing, in everyday speech, in theater, as a means of education.

The life credo of Sevdalina Panayotova, a third-generation teacher, was that education and upbringing are key factors in the formation of one’s personality and the path to emancipation. Education in the sense of knowledge and scientific approach; analytical thinking in the sense of observance of basic moral norms, regardless of the circumstances. Therefore, developing critical thinking, i.e. questioning the "truths" imposed from the top, among friends, relatives, and above all students, was the Sevdalina Panayotova’s approach to opposition. The forms of her cultural opposition were various: organizing a literary circle, preparing theatrical performances, writing scenes and, in particular, teaching high school with an approach different from those officially accepted. As a teacher, screenwriter, and theater director, Sevdalina Panayotova created plays that were hindered by state institutions, but which have provided different generations with courage and anti-totalitarian thinking.