When editing the samizdat the editors realised that they were unable to produce a radical change in their minority situation on their own, since this required a democratic turn within the country. This led to the idea of the community of fate: the discrimination they were subjected to would only cease if the ethnic majority also got rid of the suffocating dictatorship. So there was an overlap between the minorities and those democratic, non-politicising Romanian individuals, who, although they did not feel the minority oppression for themselves, were nonetheless suffering from the lack of democracy. The editors were guided by the conception of finding sympathisers to resonate with their dissatisfaction. Therefore the magazine was partly bilingual. Whenever they felt the need, they not only translated into Hungarian certain important writings of their Romanian fellow ideologists, but also published the Romanian versions of these texts. In the person of Doina Cornea – who counted as an example for her attitude, spirit of sacrifice, and criticism of the system – they found a colleague who at the beginning had not even suspected that she was cooperating with them as they had borrowed several of her declarations without her knowledge, primarily from Radio Free Europe, and corresponded with her in the samizdat.

The first step of the Hungarian–Romanian union of efforts was the publication of the leaflet entitled Fraților – Testvérek in the spring of 1988, in which linguist Éva Cs. Gyimesi together with puppeteer, artist, and prose writer Ivan Chelu protested against the potential demolitions of the Transylvanian villages. As a debut of the relationship established with Doina Cornea they first published a real conversation between her and another (unidentified) Romanian intellectual entitled “Találkozás Doina Corneával” (Meeting with Doina Cornea), and then published Cornea’s text entitled “Doina Cornea levele a Szentatyához” (Doina Cornea’s letter to the Holy Father). The views of the editors and those of Cornea had much in common, though the former had certain reservations regarding the way the latter interpreted the contemporary situation. In spite of all this what really mattered was that finally there was a Romanian intellectual with whom they agreed on a number of issues and in certain cases they could confront each other “in a way that was usual among members of the same team when it came to clarifying ideas.” They accepted Cornea’s call for solidarity and unity irrespective of nationality and agreed without reservations upon her encouragement to avoid any form of violence. They were convinced, along with Cornea, that there was an institutional crisis in Romania and that behind this the Securitate was operating everywhere. They were also in agreement that the laws of the country must be abided by and that the same applied to international treaties. However, the editors went further: they believed that this was not enough for the Hungarian minority and that there was a need for basic legal arrangements, which ensured not “socialist” but real democracy, and not only for Hungarians, but also for every Romanian citizen. They agreed with Cornea’s idea of stimulation to action, though they held different views as regards the driving force behind this and what this would mean in practice. They acknowledged that Cornea did not want to be a politician: she was primarily interested in the moral aspect and according to her there was mainly a need for moral renewal, since without that political change was impossible. Nonetheless, the editors wanted to take political action, at least through the medium of the printed word. They doubted that the elimination of the moral recession would lead to the solution of the political crisis. At the same time they accepted the fact that under the given circumstances they all had to serve as witnesses and that this should be followed by action.

Afterwards a dialogue began with Doina Cornea, who by then was a dissident personality known across Europe. The first tone of this dialogue was set by Éva Cs. Gyimesi by means of an open letter, entitled “Nyílt Levél Doina Corneának” (Open letter to Doina Cornea), which was published in both Hungarian and Romanian. The addressee could identify the sender “without a signature” on the basis of the letter’s contents and their shared experiences. In reality this was a one-sided dialogue, in fact the collaborators of the samizdat reflected on several of Doina Cornea’s affirmations, but they did not receive a reply.

In her letter, Gyimesi includes her carefully formulated reservations. The “anonymous” correspondent considers it strange that her addressee does not want to build a closer relationship with the Hungarians on the grounds that her fellow Romanians would accuse her of “having sold herself to strangers.” The question arises: does she refuse to act in an organised way in general or is it them, the “strangers” she avoids joining forces with? Cornea felt deeply hurt because once she had indeed been the victim of a rude offence committed by one person due to her nationality, but Gyimesi warns her: crimes committed by individuals should not constitute a reason for collectively blaming an entire community. For the editors, this was a guiding principle. There were numerous offences committed by Romanians that they were fully aware of and protested against, but they never intended to turn these reprehensions into anti-Romanian acts. This is how they expected to be treated by the other side as well (Doina Cornea included). This was followed by the most essential message conveyed by Gyimesi’s letter which focused on the reconciliation between Hungarians and Romanians in the spirit of the ideology of Transylvanism. Afterwards, the correspondence between the editorial team of

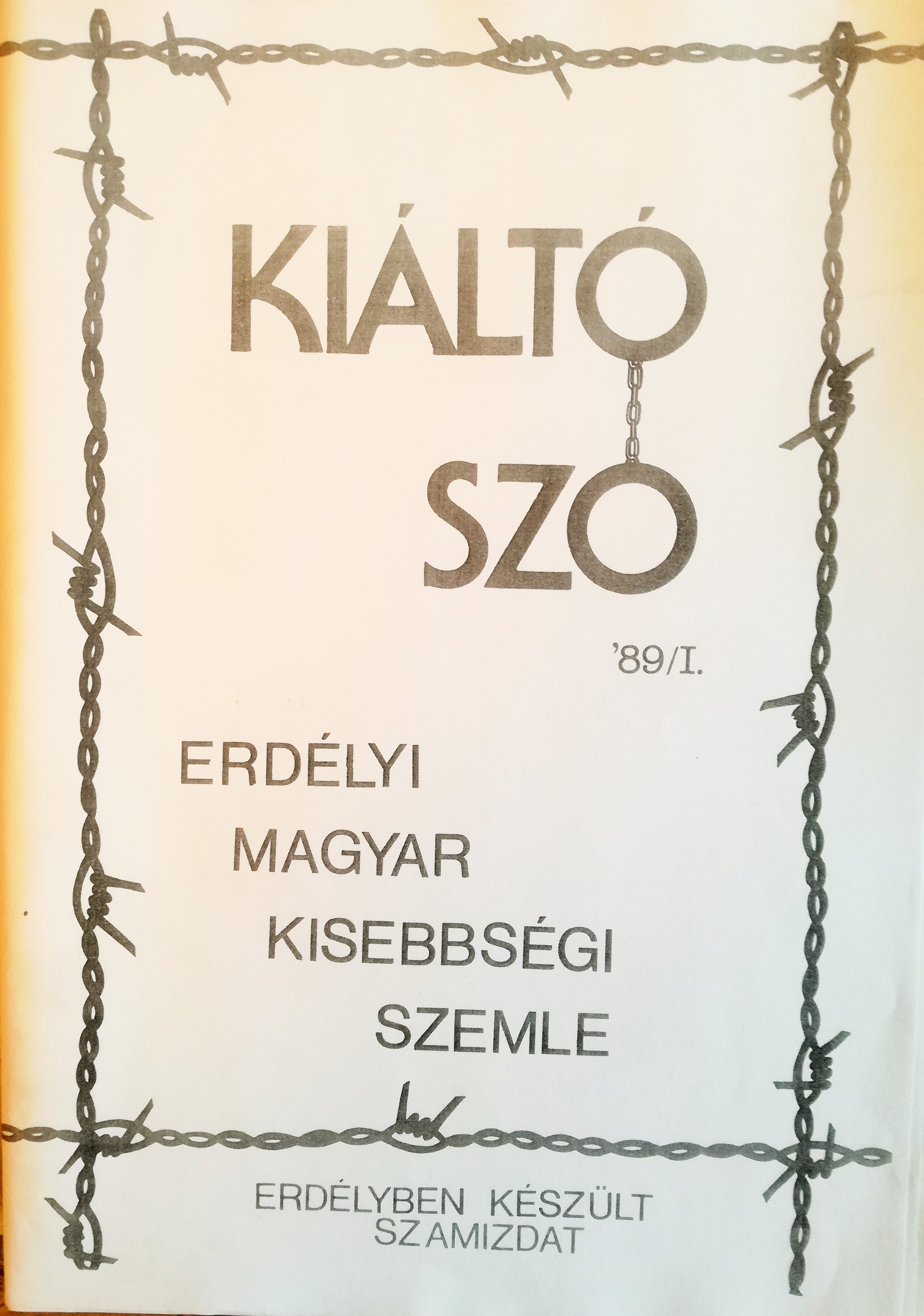

Kiáltó Szó and Doina Cornea followed a broader course. In the following editions which failed to be published, a further three epistles sought to further clarify Doina Cornea’s views broadcast by Western radio stations and argued that these views actually complied with the conception of the editorial team.