Ion Monoran (b. 18 January 1953, Ciacova, Timiș county – d. 2 December 1993, Timișoara) was not only a representative personality for the culture circles in the Banat that were unaligned to the official line of the communist regime, but was also the demonstrator who was able to catalyse the spontaneous protest in Timișoara on 16 December 1989 and transform it into what is known as the Romanian Revolution.

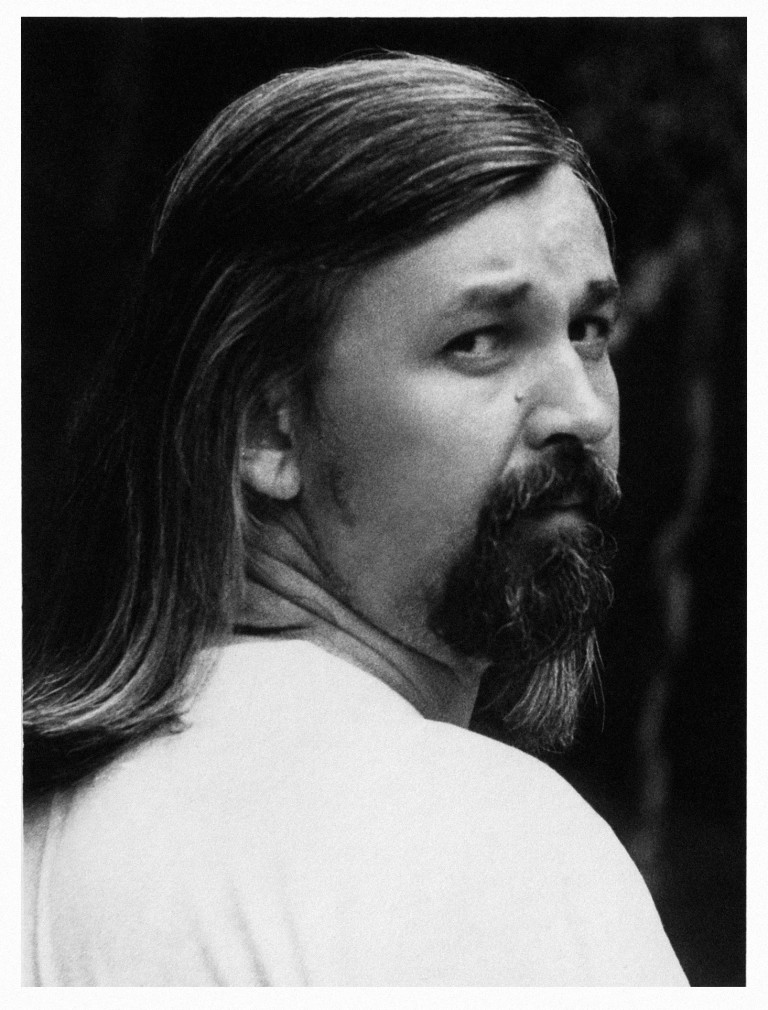

A rebellious poet, an awkward figure for the official cultural canons of the communist period, Ion Monoran was “a Bohemian apparition in the paralytic landscape of committed literature, a poet with long hair, undomesticated by the Ceauşescuist theses, tolerated but rarely published, a problem-writer for the censors of the magazines [intended for young people] Forum Studențesc, Amfiteatru and Orizont. A leader of one of these magazines expressed at one point his concern regarding the sort of unaligned poetry that Ion Monoran was writing with a question that was to remain famous in Timișoara cultural circles: ‘What’s this, mate? You want to put the boot into poetry?’”(Armanca 2011, 55)

As far as the official communist cultural canons were concerned, the appreciation could not have been more just: Ion Monoran’s poetry was not only nonconformist, but also ironic and contestational towards the communist regime. Consequently, prior to 1989 Ion Monoran was very seldom published in the press, and his first volume of poems would appear only after the fall of communism, but also, unfortunately, after his own early death.

In spite of the fact that he was practically without a body of published work, Ion Monoran was one of the most well-known representatives of the cultural Bohemia of Timişoara before 1989. This cultural grouping of professional writers and non-professionals with literary aspirations constituted a form of resistance in the face of official communist propaganda. The representatives of this grouping, who numbered no more than fourteen or fifteen, had a number of meeting places: either the Pavel Dan Literary Circle, or the Cina restaurant, or the cemetery of Timișoara’s Rusu-Șirianu district. Timişoara’s cultural Bohemians also regularly met in the basement boiler-room of a four-storey apartment block, where Ion Monoran had his place of work. Obliged to find employment as an unskilled worker due to his expulsion from high school following his failed attempt to flee the country, Monoran was all his life downgraded in the social order. This did not prevent him from being recognised in the unofficial hierarchy of Timişoara’s Bohemians as a charismatic poet and member with equal rights, even a leader, of a group of writers who met at intervals. In addition to Monoran, the group was made up of: Traian Dorgoșan, Valeriu Drumeș, Ioan Crăciun, Rodion Vasilache, Nicu Stoia, Viorel Marineasa, Daniel Vighi, Gheorghe Pruncuț, Eugen Bunaru, Șerban Foarță, and Petru Ilieșu. These Timişoara Bohemians were perceived in local and national cultural circles as being unaligned to the official canons of the communist regime.

Ion Monoran already had a reputation as a rebel before he began to participate regularly in the informal meetings of the Timişoara cultural Bohemians. Basically, his option for a nonconformist career had its origin in his attempt in 1971 to cross the border illicitly. He was then in his final year of high school, and as a result of his “attempted flight” he was expelled. In the declaration that he gave to the investigators, which has been recovered by his family in the CNSAS Archive, Monoran mentioned that he wanted to leave the country in order to travel and to write poetry. For this reason, he only finished high school seven years later, by taking evening classes. In the meantime, he was employed as a worker and carried out his military service in construction, in conditions dangerous to his health, in a military unit where he worked alongside many common-law prisoners.

In the 1980s, Monoran became a well-known name in the alternative cultural world of the Banat, and especially Timişoara. He wrote a lot, although he hardly published anything. His work has a strong note of contestation of the communist regime, as would later be noted in the General Dictionary of Romanian Literature, published under the aegis of the Romanian Academy: “A component of the eighties generation, refusing any compromise, Monoran postponed his debut beyond the limits of his own life. His impulsive, abrupt, and often contradictory poetry, as well as his essentially contestational writing, maintain a permanent state of conflict, fitting the experience of a free, misunderstood mind” (Dicționarul general al literaturii române 2006, Vol. 4, 436-37).

In December 1989, Ion Monoran behaved in an extraordinary way during the first days of the Romanian Revolution. Retrospectively, in an interview for Radio Timișoara, he gave his perspective on those crucial moments for the transformation of an unorganised demonstration into an anti-regime protest: “When I got to Maria Square, there were no more than twenty-five people around Pastor Tőkés’s house. I went in among them and I said to them: ‘We’ve got to do something, but for that we need leaders, otherwise we’ll have the same fate as those in Braşov, in 1987! [...] The first thing we need to do is to stop the trams, so we can be as many as possible, and then all of us to go to the Party County Committee!’ I stopped the tram that was coming from the North Railway Station. The driver, a young man of twenty-five to thirty dressed in a denim suit, was scared and started crying and begging us to let him go. I told him to get into the car and we took down the pantograph, calling the people in the tram to join us. As if by a miracle, not one passenger protested, and they all joined us. [...] In a few minutes, 800 to 1,000 people had gathered in the square, and their number was growing at a dizzying rate. The crowd started to shout out slogans like: ‘Freedom!’, ‘We want heat!’, or ‘We want food for our children!’” Monoran’s recollection for the local radio station was replayed posthumously on the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the fall of communism in Romania (Both 2014).

In recognition of his crucial contribution to the outbreak of the Revolution of 1989, Ion Monoran was made, post-mortem, an Honoured Citizen of the city of Timişoara. A bust cast in bronze of the rebellious poet and revolutionary Monoran has been erected very close to the place where he stopped the tram in December 1989, and his name is now borne by the reading room of the Revolution Memorial in Timişoara and by a street in the city.