Mihai Manea (b. 5 April 1955, Bucharest) was educated at a vocational school. In 1982, together with a number of colleagues, he founded a rock band, Barock Group, without the knowledge of the Party Committee in the factory where he was employed at the time, the Machine Tools and Aggregates Plant Bucharest (IMUAB). Initiating and pursuing such musical activities was not forbidden, but it required the approval in principle of the local Party organization. “The people in the plant, especially those from the Party who gave approval in the factory for artistic activities, found out about us directly from the newspaper. But there was no trouble. On the contrary, they immediately adopted us, they were proud of us. There were all sorts in the Romanian Communist Party.” This may be explained by the fact that all communist plants had to send participants from among their employees to the national Cântarea României (Song of Romania) festival. Founded in 1976, and conceived as a festival for amateurs and professionals, Cântarea României in fact destroyed professional standards and promoted shows eulogizing the Romanian Communist Party and its leadership, finally becoming an important vehicle for the personality cult of Nicolae Ceaușescu. At the same time, the local phases were much less ideologized than those at county or national level, so for many young people, taking part in this festival was a welcome break from their regular workplace activity (D. Petrescu 2010, 304–307).

In his employment card, Mihai Manea was categorized at IMUAB as “cutting-tool operator,” denoting a highly skilled worker. It is a trade that he has practised very little, because in fact a large part of his professional activity has been connected with the production of and technical support for numerous concerts. For a short time, he also worked at the Research Institute for Household Articles and Toys in Bucharest. Like many other young people, Mihai Manea had multiple ambitions: he toyed with science fiction writing, frequenting several clubs (and chairing one such writers’ group, which operated within the IMUAB), with a sporting career (he is a former rugby-player), and, for a short time, with cinema (directing short and very short films as a member of cinema clubs in Bucharest).

At the same plant where he was employed until 1990, Mihai Manea was the coordinator, in both the technical and the editorial senses, of the amplification post through which “cultural-artistic programmes” were transmitted for the benefit of the institution. “It’s interesting that they let me deal with it, that they had the trust to leave something like that in my hands – and I say this because I wasn’t a Party member. Only when I was young, I was, for a short time, a member of the Union of Communist Youth, but I was never a full member of the Romanian Communist Party. I kept slipping through the net.” In communist Romania, all young people aged between 14 and 30 were in the Union of Communist Youth (UTC), but of these only some became members of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR). In other words, inclusion in the UTC was obligatory and automatic, but PCR membership was conditional. In the 1980s, the selection criteria were lowered so much that only those who did not want to did not become Party members. Most joined out of opportunism, because belonging to the PCR gave access to many privileges, from the allocation of an apartment to approval for going abroad as a tourist.

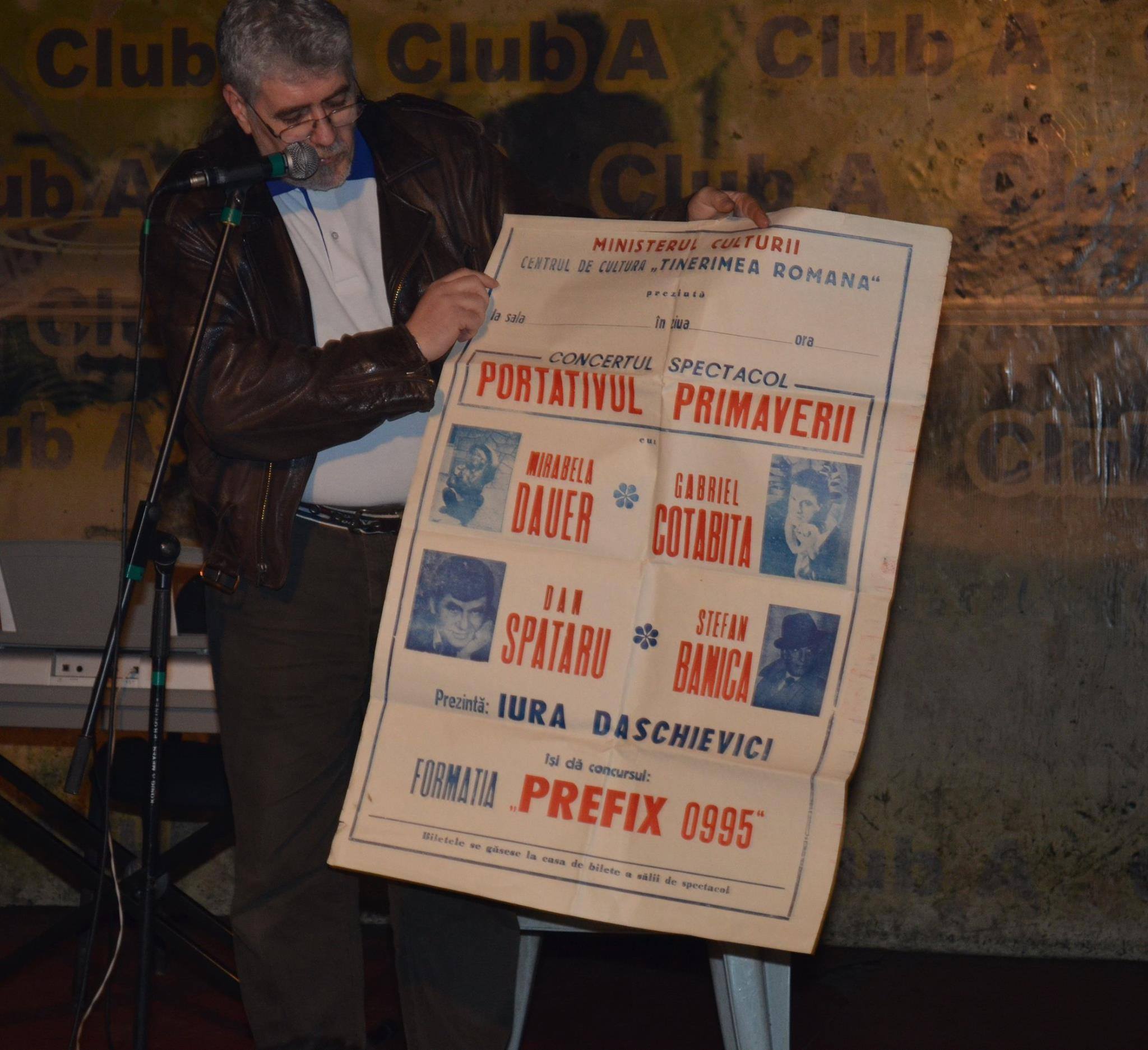

For more than two and a half decades, Mihai Manea has worked as a technician at the Romanian Youth National Art Centre, an institution under the aegis of the Ministry of Culture, and he continues to maintain his passion for music and concerts, including at a professional level. It was basically only after the fall of communism that Mihai Manea’s life-long passion turned from amateurism to profession. “As young rebel I fingered an instrument too… the bass, but satisfaction came only when I began to understand that you can be a creator if you are part of the technical team. And so I moved on to pressing buttons, and gradually had the chance to work in big musical productions. You know, behind the scenes, when you’re inside the show, there’s a lot of adrenaline and sensations that can’t be described in words. Behind the scenes there’s a lot of work and there’s an army of people who always have something to do. There are thousands of metres of cables for sound and electricity, there are scaffolds and cranes, everywhere you find amplifiers, sound processors, and lighting controls. You come across hundreds of boxes, ventilators, smoke generators, pyrotechnics, gas for flames, scenery, and there are people who know about all these things and work with them while taking care for the safety of others. On the stage, on the roof, and under the stage, nothing is placed at random. How could I describe this beautiful madness? There aren’t words enough to express what you feel when you’re there, with people who have to make it all work.” Thus Mihai Manea concludes his confession about what is both his passion and his profession. Like many others who developed various hobbies in their free time by speculating on the freedoms permitted by the regime in the grey zone of tolerance, Mihai Manea represents a model of the post-December 1989 transformation of a personal collecting passion, in this case derived from his passion for music, into a profession.