The Mihajlo Mihajlov collection consists of 42 standard and 23 larger than standard boxes. It is written in several languages: Serbian, Serbo-Croatian, Russian, English and German. The collection is divided into several sections: personal data, correspondence, personal notes, speeches and articles, business cards, writings by other author about Mihajlov, works and articles by other authors, and audiovisual records.

The first section of the records, which includes three archival boxes, contains Mihajlov's personal documentation, biographies, bibliographies and the address book of the people with whom he communicated. Apart from materials from his public activity, there are also personal documents and documents from his family life, related to his mother Vera Mihajlov and sister Maria Ivušić.

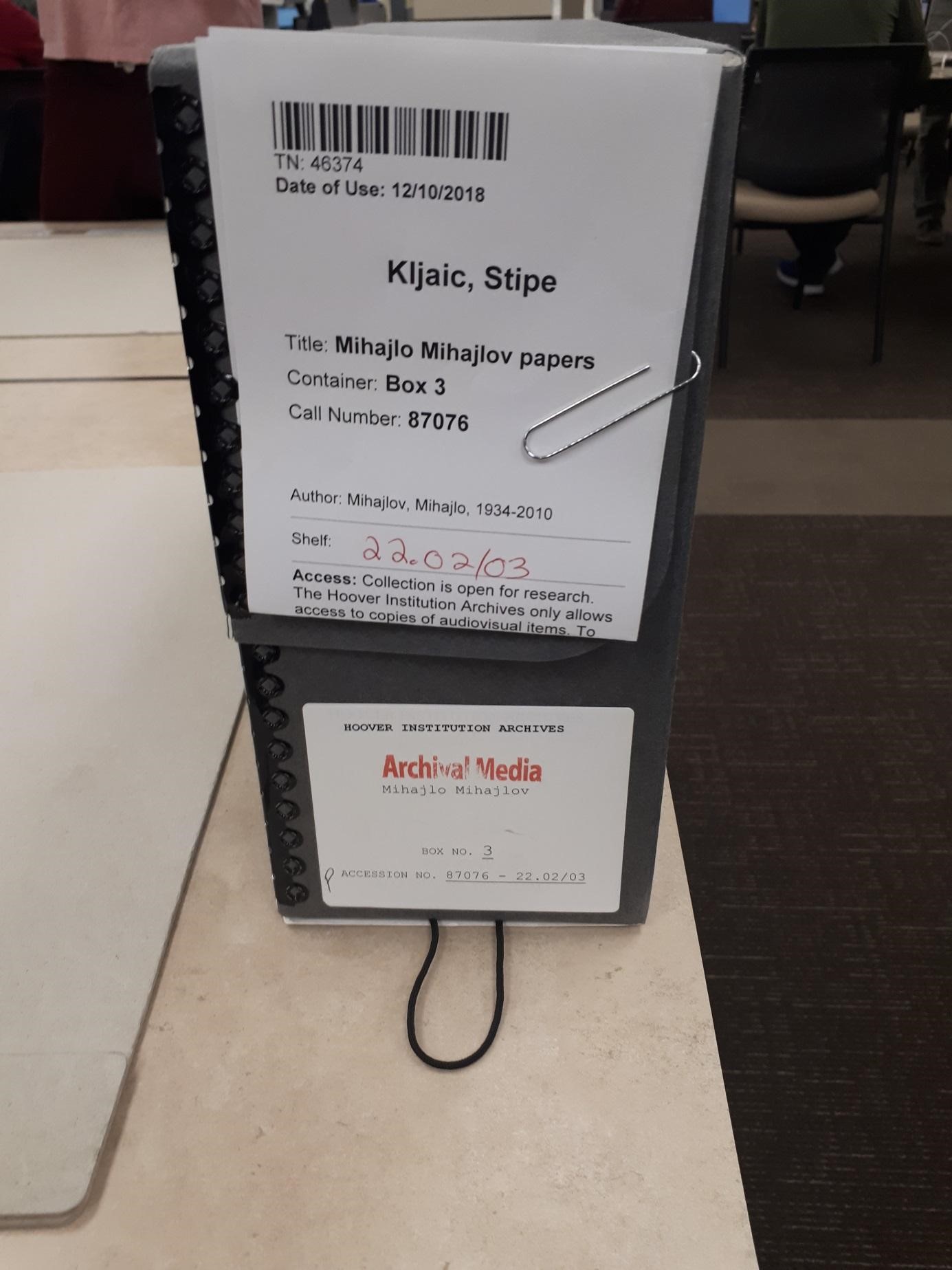

Among the most interesting materials in the first part of the materials are documents from political trials, which were directed against Mihajlov in the Yugoslav courts in the 1960s and 1970s. These records are in box 3 and include various documents from 1965 to 1975, as well as Mihajlov's written communications to the authorities (Tito) and tribunals, most often in the form of appeals or requests to improve his status as a convicted person. During his second period of imprisonment in Srijemska Mitrovica in the 1970s, Mihajlov even staged a hunger strike to improve his status. As an intellectual, he was particularly sensitive to access to books under restricted prison conditions, so besides his demands to be released from jail and be allowed to leave the country, the most important demand to the prison authorities was to read as many different books and other written materials as possible. Apart from his specialization and interest in Russian literature and the Yugoslav and Russian dissident movement, Mihajlov intensively read religious literature by studying not only books on Christian issues, but also those on Indian philosophy and Eastern religions in general (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 3).

Furthermore, from box 3 to 11 this collection contains correspondence with numerous institutions and individuals in the period from 1965 to 2010. Mihajlov co-operated mostly with the Serbian, Croatian and Russian dissident scene (Jovan Barovic, Vadim Belotserkovsky, Vera Piroskov, Grigory Svirsky, Andrei Sinyavsky, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Predrag Palavestra, Mirko Vidović, Ivo Glowatzky, Franjo Tudjman and others). He also corresponded with the prominent political figures of his time, such as Josip Broz Tito, US President Jimmy Carter, and Britain’s Prince Charles, who was also interested in his case of political persecution (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 8).

Box 9 contains lists of political prisoners and political trials in Yugoslavia and books and journals banned since 1945, which was used by Mihajlov as an argument to reveal to the Western public insufficiently known facts about dissident movement in Tito's Yugoslavia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The same box contains the correspondence and debate between Djilas and Mihajlov in a letter dated February 27, 1984, in which Djilas wants him to remove his name from the board of CADDY. The disagreement with Mihajlov occurred in Belgrade several years after 1979, when together with Momčilo Selić, who later replaced Djilas on the board of CADDY, they published the samizdat called Timepiece (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 13). It led to Selić’s punishment for its unlawful publication. In addition to mutual quarrels, Mihajlov came into conflict with Djilas because he believed that as a dissident he did not sufficiently recognize the power of religion in the struggle against Marxist regimes (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 9).

Box 11, besides the letters to President Tito, also contains Djilas' letters to Tito, in which they advocated improving his status and release from prison in the second half of the 1970s (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 11). In the same box there are numerous materials and notes he collected to write his doctoral dissertation. Above all, there are commentaries on the work of Dostoyevsky. Box 12 notably contains the “Answers to Questions from Aleksa Djilas” in 1982, where he explained to the younger Djilas why Yugoslavia, unlike the Eastern Bloc countries, did not have a very robust and influential dissident movement. Mihajlov was aware that if Croatian and Serbian dissidents could not overcome national tensions and historical conflicts and unit, the Yugoslav project would not survive after the removal of communists from power.

In this context, he mentioned the positive example of Croatian dissident Marko Veselica, who first took the initiative for cooperation between dissidents in Belgrade and Zagreb. Mihailov himself was present at such a meeting in Zagreb in April 1978 before going into exile. It was attended by Marko Veselica, Vlado Gotovac and Franjo Tudjman from Zagreb, and besides Mihajlov, Djilas, attorney Jovan Barović and Dragoljub Ignjatović from Belgrade. He regarded Veselica’s role in this as the main reason why he was subsequently sentenced to eleven years in prison. Likewise, the dubious circumstances in which Barović perished in 1979 also had an epilogue which brought Croatian and Serbian dissidents together, Mihajlov concluded. In his response to Aleksa Djilas’ questions, he pointed to the primacy of the democratic principle in his political views when a solution to the Yugoslav crisis was in question. Therefore, he reasoned that support for a united Yugoslav state could not be a criterion for the division into “democratic and undemocratic nationalists,” since he was personally ready to accept a democratic Croatia rather than an authoritarian Yugoslavia (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 12).

When it comes to the dissident movement, Mihajlov considered it primarily an expression of the activism of intellectuals throughout the communist bloc, except for the “people’s springs” which occurred in both Poland and Hungary in 1956 and in Czechoslovakia in 1968. Mihajlov was interviewed by Djilas’ son Aleksa about the main reasons for the meagre development of the dissident movement in Yugoslavia compared to its great expansion since the 1960s in other parts of the Eastern Europe.

In the first place, there was the conflict with Stalin in 1948, which prompted Yugoslavia to “liberalize” in many areas, especially in the sphere of culture, especially after the Ljubljana Congress of Yugoslav Writers in 1952. Thus, for example, painting, music and poetry distanced themselves somewhat from the embrace of the ideological monopoly, a process that began in the Soviet Union only in the 1980s.

Another major obstacle to the development of the dissident movement was the national question in Yugoslavia, which constantly emphasized the national uniqueness of each people as the most important political and cultural issue, which made it difficult for dissidents from different national groups to come together (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, Box 12).

And thirdly, Mihajlov cited as the third reason the West’s external support for the communist regime in Yugoslavia, so that dissidents in the latter country could not secure the same moral support of the West as that given to Soviet and Eastern European dissidents. Moreover, until the 1980s, the West did not pay any attention to systematic violations of human rights and the persecution of writers and intellectuals due to their intellectual work in Yugoslavia. Excepting Djilas and himself, he believed that this was a consequence of the fact that Djilas was one of the pillars of Tito’s regime. On the other hand, in his personal case, the Western public’s attention was only attracted because he criticized the Soviet Union. The cases of Ivan Stevan Ivanović and Franjo Tudjman, for instance, did not garner any attention from the Western press, although Mihajlov's CADDY notified numerous US institutions, including the press, and influential policymakers of Tuđman’s case (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 12).

However, Mihajlov believed that his arrival in US and the launch of CADDY had altered the situation, and that since the 1980s the dissident movement in Yugoslavia gained more strength than it had in the preceding two decades when the Western public had less interest in it. He concluded that “I am not condemning the Yugoslav intelligentsia in any way and think that is no less free than its Soviet, Polish or Czech counterparts.” In his opinion, these specific circumstances were responsible for the unique course of Yugoslav socialism since 1948, which inevitably influenced the slightly different character and dynamics of the Yugoslav dissident movement, unlike other countries of the Eastern bloc (Mihajlo Mihajlov Papers, box 12).

The third part of the collection contains Mihajlov's manuscripts, articles, essays, lectures, speeches and his own books. There are also various works and writings by other authors in boxes 34 through 42. Among the manuscripts, the materials he collected for his doctoral dissertation on Dostoyevsky stand out. Materials published during his stay abroad from 1979 onward in various leaflets and magazines in several different languages - Serbian, Croatian, Russian, English, Finnish, Czech, French, Italian, Polish and Spanish – are in the group of articles and essays in boxes 15 through 29. Box 28 contains an English translation of “Moscow Summer” from 1965, because he was politically persecuted in Yugoslavia in the 1960s. Box 29 contains Mihajlov’s most famous and most important works, such as “Russian Themes” from 1968 and “Underground Notes” from 1970, both in English, and “Unscientific Thoughts” from 1979 in Russian. In addition, the books and essays from his later phase, such as “Nietzsche in Russia” (1986), were concerned with the influence of Nietzsche's philosophy on Russian modernism in the fin de siècle period. The manuscript for the Serbian edition entitled “Repeat Thoughts” (2008) provides an overview of the main dissidents in Yugoslavia and his personal contribution to dissident movement.

The fourth part of the materials in the boxes from 30 to 33 consists of articles and essays written by various authors in different languages about Mihajlov and his case and his works. It is evident from them that Mihajlov, after being exiled from Yugoslavia, mostly cooperated with a circle of mainly Serbian pro-Yugoslav émigrés gathered around the magazine Naša reč (Our Word) and individuals such as Desimir Tosic and Ivan Stevan (Vane) Ivanovic, who advocated the preservation of Yugoslavia through their émigré Democratic Alternative initiative and removal of the Yugoslav communists from power. Thus, box 30 contains collected texts in which Yugoslavia's newspapers and journals particularly attacked Mihajlov in the 1960s. Among them, the most interesting text is from a Belgrade magazine Gledište under the headline “A Pamphlet Against the October Revolution.”

Certainly interesting in this part of the collection is the article from the Yugoslav press in the autumn of 1990 about Mihajlov, when he briefly returned after 12 years in exile. The Belgrade weekly magazine Duga carried an interview with him under the headline “The Return of Mihailo Mihajlov.” In it, Mihajlov clearly expressed his political desire to preserve Yugoslav unity and prevent the independence of its republics, which was then in line with the official policy of Slobodan Milošević. The fifth part of the collection includes business cards with contact information and research notes and writings in boxes 43 through 47. The last section of the collection covers audiovisual and digital materials, which are arranged in boxes 48 through 64, consisting of television interviews granted by Mihajlov during his life, and especially from the last period after his return to Serbia since 2001.