The Șoltoianu ad-hoc collection was defined by separating it from the collection of judicial files created by the Soviet Moldavian KGB concerning persons who were subject to political repression under the communist regime. The case of Alexandru Șoltoianu is closely linked to the larger Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur affair and is usually viewed as part of the fledgling nationalist resistance movement in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Despite the undeniable connections between these two cases (e.g., Șoltoianu was one of the signatories of the appeal addressed by the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group to Nicolae Ceaușescu), Șoltoianu’s activities in fact represent a parallel attempt at articulating a nationally oriented oppositional message. Șoltoianu was arrested in January 1972, together with the members of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, but his trial was immediately separated into an individual case. He was accused of displaying persistent “nationalist and anti-Soviet convictions.” His subversive activities were purportedly directed toward “the creation of an underground nationalist organisation aimed at fighting against the existing social order of the USSR and at undermining Soviet power.” However, this organisation, tentatively called “National Rebirth of Moldavia” (Renașterea Națională a Moldovei, RNM) had a different intended structure and in fact never developed beyond a small group of Moldovan intellectuals who formed a loose informal network around Șoltoianu. This organisation should have gradually grown on the basis of a number of student-based Moldavian national associations that were to spring up in all the Soviet cities where significant cohorts of Moldavian students were attending various higher educational institutions (e.g., in Moscow, Leningrad, Lvov, Chernivtsi / Cernăuți, Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, Ismail, and Belgorod-Dnestrovskii). In fact, Șoltoianu made rather feeble and inconsistent attempts to mobilise a few dozen Moldavian students in the first four cities, where he established informal contacts with a number of like-minded young intellectuals. In a clear reference to the first stirrings of the Romanian national movement in Bessarabia during the last years of the nineteenth century, Șoltoianu intended to create a network of student “national associations” (zemliachestva) which would represent the initial cells of the future mass political party. He in fact succeeded in establishing such an association in Moscow in early 1963. Its activities focused on a variety of national-cultural meetings and informal gatherings, although Șoltoianu made some efforts to steer it in a more political direction. After 1964, his activities mostly focused on the consolidation of the small network of his collaborators through periodic personal meetings and written correspondence. However, this network never coalesced into a real tightly knit group, despite Șoltoianu’s intentions and efforts.

The documents grouped in this collection consist of two main categories. The first category comprises the various texts produced by Șoltoianu in the decade preceding his arrest (i.e., between 1961 and 1971). Unlike his peers in the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, Șoltoianu did not attempt to spread his writings systematically to a wider audience, only sharing them with a select few of his friends and acquaintances in intellectual milieus. According to his own testimony, Șoltoianu intended to write a comprehensive historical-political treatise, “unmasking” the discriminatory and repressive policies of the Soviet regime in the field of nationalities policy in Soviet Moldavia. His fragmentary sketches, notes, and drafts amounted to over five thousand pages of written materials, but were never developed into a coherent text and remained at the stage of unfulfilled projects. Șoltoianu’s approach was more historically minded than in other similar cases, given his professional background and extensive reading in Romanian history. Both in his written output and in various conversations with his informal network of friends and acquaintances, he openly condemned the policies of Russification, forcible assimilation, and “de-nationalisation” pursued by the Soviet authorities in the MSSR, labelling them “colonial” and drawing direct parallels with the similar policies of the Russian Empire. Șoltoianu’s discourse is in fact a curious mixture of anti-imperialist rhetoric that he drew from contemporary Soviet sources and of ethnically charged accusations against the “Russians,” whom he saw as “occupiers.” He accused them of discriminating against the Moldavians on a national basis and of oppressing the republic’s majority ethnic group linguistically and institutionally (through the imposition of foreign cadres and managing personnel at all levels). Șoltoianu’s proposed solution was secession from the USSR and unification with Romania, but he emphasised a much more activist and at times even violent strategy in order to achieve this goal, in comparison with the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group. His projected mass political party was to reach the fantastic figure of 250,000 members, thus amounting to a popular anti-regime movement of impressive proportions. Although these plans remained purely theoretical, it is clear that Șoltoianu envisaged an unprecedented degree of national mobilisation, probably drawing on nineteenth-century Central and East European parallels. Romanian nationalism was his main source and model for imitation. However, his projected “national awakening” had more in common with the ideal vision of a mass-based “popular” nationalism (similar to the nineteenth-century Polish, Czech or Hungarian examples or, in the Soviet context, to the Baltic states) than with the rather insignificant Bessarabian national movement prior to 1917. The unrealistic and utopian character of his schemes was compounded by his idea to send his future treatise to the UN as a “manifesto” of the whole “Moldavian nation” in a plea for assistance from the international community. Another significant component of his anti-Soviet stance concerned his virulent criticism of Soviet foreign policy, especially in the context of the USSR’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. Starting from 1964, he was already criticising Soviet “economic imperialism,” which had allegedly turned the COMECON into a tool for Soviet domination over the satellite states of Eastern Europe. His ideas became radicalised in the summer of 1968. Probably under the impression of Romania’s “dissident” position and due to his access to Romanian press materials, Șoltoianu openly denounced the Soviet invasion as “violating international law” and “depriving Czechoslovakia of its state sovereignty,” contrary to the official position of the Soviet propaganda machine. His vision of the USSR as a “colonial empire” thus applied both to the fields of domestic and of foreign policy. The papers produced by Șoltoianu are mostly fragments written by hand and scattered throughout several dozen notebooks that he intended as future drafts of his comprehensive treatise (which was never finished). A large portion of these texts are annotations and commentaries on his extensive readings, as well as summaries or clippings of newspaper articles or press digest materials.

The second large category of documents in the collection consists of interrogations and testimonies provided by Șoltoianu himself and his closest collaborators during the inquiry initiated by the KGB. Of these, only those recognised by the accused and relevant to the wider picture were selected in this ad-hoc collection. Although produced under pressure at the KGB headquarters, these signed testimonies can be regarded as valuable sources of information on Șoltoianu’s projects and activities. These testimonies are especially valuable in order to trace the gradual development of Șoltoianu’s views and his informal networks. It appears that his conversion to nationalism occurred in Moscow, where he was a student at the State Institute for International Relations (MGIMO) between 1959 and 1964. This happened under the influence of his fellow students from other socialist countries (including Romania) and was stimulated by the comparatively liberal atmosphere at the Institute. Starting from the early 1960s, he started recruiting other young intellectuals of Moldavian origin as a part of his larger plan to form a resistance movement to Soviet rule. In early 1963, after creating the above-mentioned student association in Moscow, he tried to spread his oppositional message among a large group of Moldavian students (about forty people) who were visiting the Soviet capital. Some of these students joined his informal circle, which he maintained for the following eight years. However, the number of his closest associates never exceeded ten to twelve people. During his brief stint as an instructor at the Chișinău State University in 1966–67, Șoltoianu tried to extend his network among local students, but his success was rather mixed. After returning to Moscow in 1968, he maintained contact with his supporters, mainly aspiring young intellectuals in the humanities, through correspondence and occasional meetings during his short trips to the MSSR. During the trial, Șoltoianu maintained that he did not actively propagate his ideas to a broader audience, but shared his plans of establishing an oppositional mass movement with only a handful of his most trusted confidants. He also attempted to mitigate his plight by claiming that his activities never targeted the Soviet regime as such and were instead aimed purely at fighting Russian ethnic domination within his native republic. Although this strategy did not work, it is revealing for Șoltoianu’s attempt to use the gaps in Soviet legislation to his advantage. Similarly to the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group, he also claimed that unification with Romania was, in itself, an acceptable option due to the latter’s status as a fellow Socialist country. Emphasising his preference for ethno-cultural nationalism, he even claimed that Romania’s entry into the USSR was an acceptable solution, as long as this guaranteed the “national survival” of the Moldavian people.

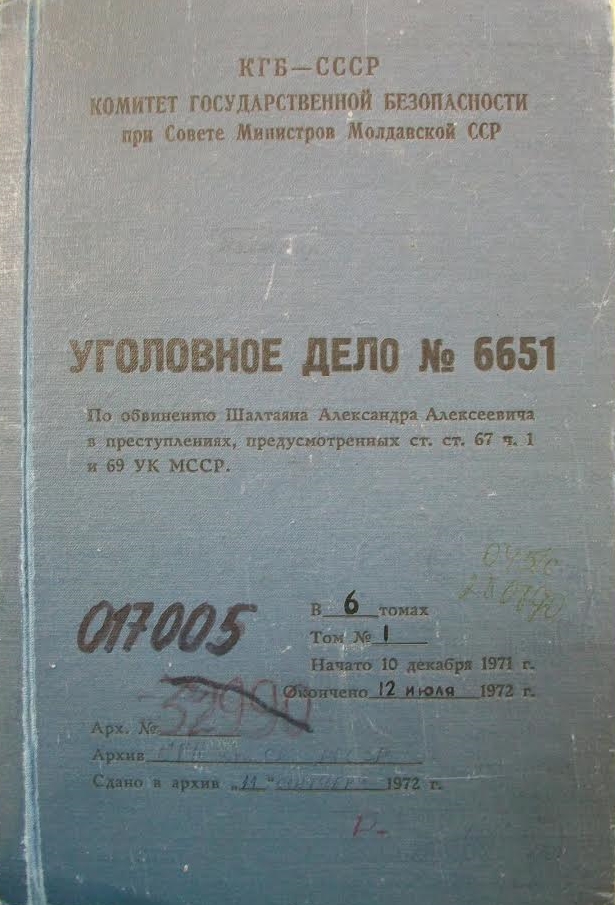

Alexandru Șoltoianu was arrested in Moscow, on January 13 1972, simultaneously with the members of the Usatiuc–Ghimpu–Graur group. His trial took place in late July and early August 1972. The Supreme Court of Justice of the MSSR completed the hearings in the case on August 2, 1972. Two days later, Șoltoianu was sentenced to six years in a high-security labour correction colony and a further term of five years of internal exile. He was rehabilitated by a special decision of the Moldovan Supreme Court in September 1990.