The Collection of János Vargha in the OSA consists of two parts. Several of the documents were donated to the organization by János Vargha himself, who was the president of the Danube Circle. Another part of the collection comes from Danube Circle activist Anna Perczel, the daughter of Károly Perczel. As an architect, Anna was also involved in the movement. These two parts of the collection got to the OSA with the help of István Rév, who knew both Vargha and Perczel well, because he was also a member of the Danube Circle for a time. Anna Perczel gave her documents and manuscripts to the OSA because she wanted the materials to be preserved by an independent, non-state organization which could ensure that they would be accessible to the public.

Environmental movements played an important role in challenges to the authoritarian regimes in the former Soviet bloc. Rapid industrialization and the race to increase production rates in the countries of the Eastern bloc had obvious environmental consequences, including widespread use of agricultural chemicals, deforestation, nuclear waste (the Chernobyl disaster being the most emblematic of all issues), and water pollution. Since the environment was seen as a “soft” issue, environmental activism offered citizens a chance to participate in politcs without being directly involved in oppositional activities. With the softening of almost all the communist regimes in Eastern Europe, however, environmental movements channeled collective dissatisfaction, and through effective mobilization, they contributed significantly to the collapse of the regimes.

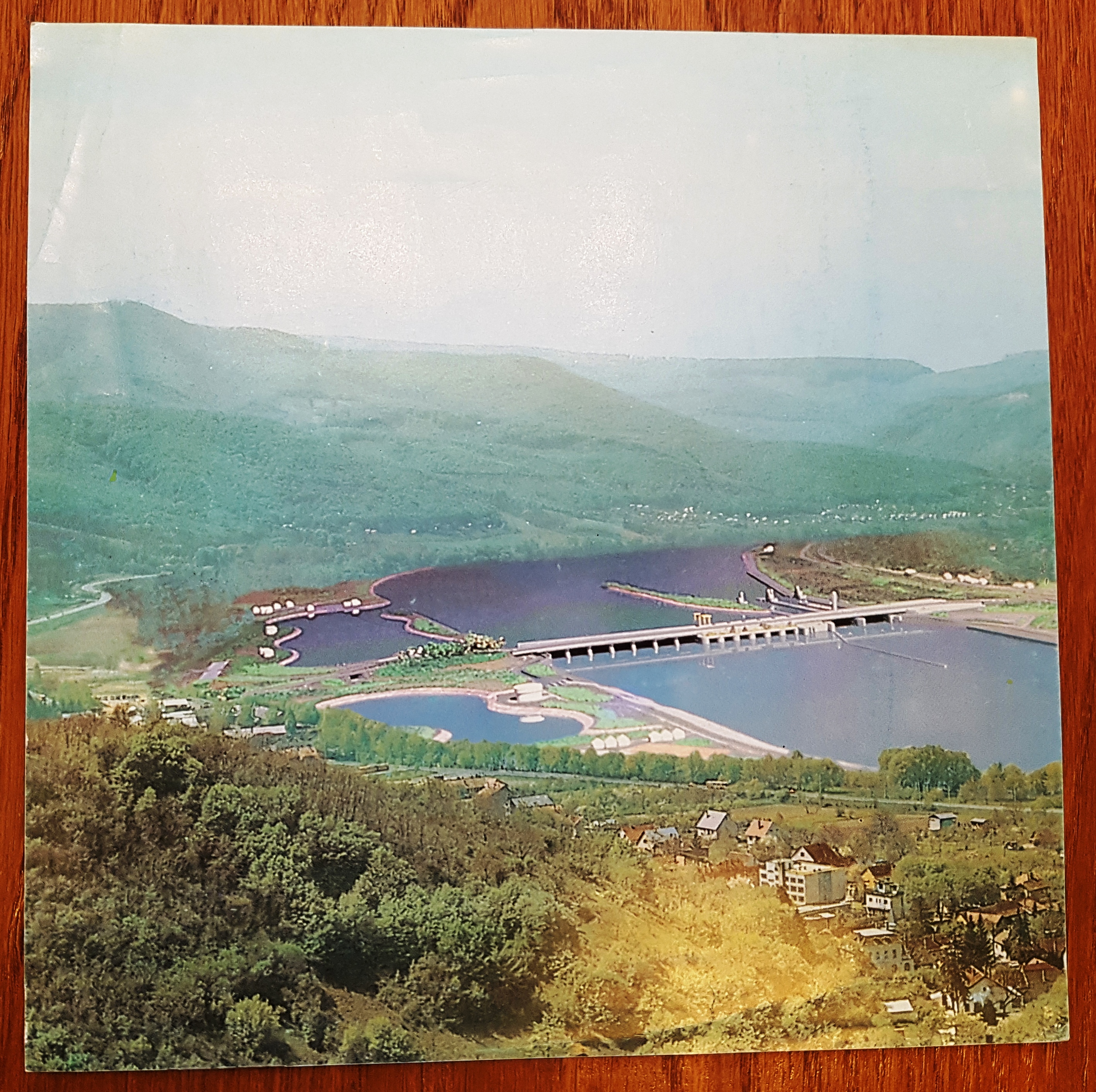

The Danube movement in Hungary called on people to protest against the construction of a dam known as the “Dunasaur,” or the dinosaur on the Danube River. The dam would have been located between Nagymaros in Hungary, and Gabcikovo on the (then) Czechoslovak side of the river Danube. The movement is of particular significance not simply because it had a major role in bringing down the regime at the end of the 1980s, but also because it left its imprint on the later evolution of civil society in Hungary.

The plant – the idea and a chronology

The plan to build a hydroelectric plant on the Danube River goes back to the 1950s, though according to some sources the initial ideas go back as far as the 1910s. After years of delay, a concrete project began to take form in the 1970s. In 1977, an agreement was signed by János Kádár of the People’s Republic of Hungary and Gustáv Husák on behalf of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic to start construction work. The goals of the project were to gain electricity power supply, to facilitate navigation of the river, and to have reasonable flood control of the river. Construction was delayed several times for financial reasons linked to the impending debt crisis facing both countries. In the early 1980s, as the environmental and economic costs of the project become more and more apparent, voices against building the dam became more and more explicit. A committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences condemned the project, and discussions about it came to the surface, with probably the most influential among them being those led by János Vargha (in 1981 and in 1984).

Károly Perczel, an engineer at the Scientific and Designer Institute of Urban Construction, was charged to prepare area planning for the envisaged water dam. Originally, Perczel supported the project, but after more profound study, he concluded that construction of the dam could trigger a disaster. His conclusions were then confirmed by his daughter, Anna Perczel, who had always opposed the river dam system. Károly Perczel prepared several studies on the probable negative consequences of the project, but the regime did not allow them to be published. In 1984, Károly Perczel took part in a public discussion at the Quay Club, where he and his daughter met biologist János Vargha and other environmentalists.

In 1984, the Danube Circle was formed as an organization aiming explicitly to raise awareness among the public and in legislation about the environmental and economic disaster that this construction would entail and to bring the entire project to a halt. The leadership of the Circle often met in Anna Perczel’s apartment in Logodi Street. In 1988, at the initiative of Anna Perczel, the Circle published a book entitled Danube – An Anthology, which originally was disseminated as a samizdat. The authors (poets, writers, environmentalists, scientists, engineers, etc.) sharply criticized the river dam system. Since the moment of its foundation, the authorities persecuted the organization and its members; public gatherings were disrupted by the police, and flyers and leaflets were banned. Nevertheless, the movement had significant influence among the Hungarian citizenry. People managed to distribute materials illegally, and the leaders of the movement began to publish a newsletter. Radio Free Europe broadcast reports about their activities, and members held lectures at universities. A documentary about the Dunasaur was screened for the public several times, and it became widely familiar before the authorities decided to ban it. The movement, moreover, gained international recognition when it was awarded the Right Livelihood Award in 1985. The movement organized illegal demonstrations, and eventually the largest demonstrations since the revolution of 1956 took place in September 1988 with 30,000 participants, forcing the government to start negotiations about the dam. This was also a possibility for the Danube Circle to put pressure on the government and demand changes, which proved to be comprehensive.

A shift finally occurred when the reform communist branch took over and Miklós Németh became prime minister. Németh dissociated himself from the official standpoint represented by the old leadership of Károly Grósz and announced Hungary’s withdrawal from the project in May 1989. He had no doubt realized the significance of the Danube question. In February 1989, 140,000 signatures were collected demanding the state put an end to the project. The Hungarian government started negotiations and finally pulled out of the agreement in 1992. The issue was far from closed, but it was reframed. Instead of an internal conflict between an oppositional movement and the authoritarian system, the dam became a foreign policy issue between Hungary and Slovakia. Even though the history of the Danube movement is undoubtedly an essential part of the history of resistance against the communist regime in Hungary, it also played a significant role later in shaping institutional politics.

Layers of the protest movement – why was it important?

The Danube movement is significant in a variety of ways. First, it enabled active opposition against the regime, as environmental activists could remain in the shadows of the grey zone for a while. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, several clubs and circles, which formed “quasi-movements,” were allowed, such as the Hungarian Ornithological Society, which was founded in 1974, or the Youth Environmental Council of the Communist Youth Organization in 1984. They were founded partly as a sign of the softening of the regime, but, as Szirmai points out, “none of them were initiatives of civil society but, on the contrary, were official and formal responses to ecological demands of society at the time.” These initiatives demonstrated popular support for environmental issues, which were not openly engaged in the criticism of the entire system. As Gille points out, the environment was also essential as a symbolic issue, since environmental catastrophes reflected the communist state’s relationship to its own citizens and the lack of willingness to provide protection. Meanwhile, the official narrative of the state represented environmental disasters as occurring only within capitalist systems.

Hungarian citizens identified with the Danube question in multiple ways, since the river and the issue of the surrounding environment could mobilize emotional, traditional, anti-systemic, and even nationalistic and patriotic values. The “melting pot” capacity of the movement mentioned in the introduction refers to the fact that the Danube movement was far from unified, as underlined by Haraszti, who regarded the movement as an “archetype of democratic pluralism” where conflicting rival groups had to cooperate. These groups included the “Blues,” who were openly against the regime, the “Greens,” who emphasized professional environmental problems, and the “Friends of the Danube,” who were pushing for a compromise. By the end of the 1980s, the movement arrived at a more general criticism of the regime, and it included leaders from the oppositional parties, which later became members of the Hungarian parliament after the first free elections in 1990, namely: the conservative MDF, the liberal SZDSZ, and the (then) liberal FIDESZ.

A less obvious element in the resistance was nationalism of patriotism, which is peculiar, as this sentiment did not become dominant in the analytical frames of the Danube movement. As diverse and colorful it was, the Hungarian opposition was marked by a division between “urban” and “rural,” and this division seems to have made it difficult to place the nationalistic voices within a predominantly urban movement. Nevertheless, the espousal of perceived national interests played an important role under the communist regime, under which the “internationalism” of the “brotherly nations” was one of the central values and any talk of national issues was taboo. This is obvious in a groundbreaking article by János Vargha (who wrote under the pseudonym Péter Kien), founder and leading figure of the Danube Circle. In the article, which was published in the samizdat journal Beszélő (Vargha, 1984), Vargha openly not only wrote about the environmental and economic consequences of the dam project, he also put forward an argument about the potential threat of Hungary losing territory to Czechoslovakia and about Czechoslovak national interests, which he characterized as contrary to Hungarian interests. This narrative was certainly present among Hungarian dissidents, but it never gained any traction in the primarily liberal atmosphere of the democratic opposition.

The birth of a movement and the importance of the Danube movement after the democratic changes

The influence of the Danube movement in the fall of the regime is almost self-evident in the literature on civil society and social movements today. A further impact of the Danube movement is found in the academic discipline of social movements studies itself. With his first analyses of the Danube movement as a new social movement, Máté Szabó and other social movement scholars sought to connect the new Hungarian social movement scene to West European traditions. Academic scholarship in this vein sought to contribute to the central project of the new democratic government by putting Hungarian movements on the map of (Western-dominated) social movement studies. On the one hand, this was an essential contribution to the existing literature on environmental movements, and it also offered a new analytical perspective on the relationship between green movements and the institutional system. On the other, this perspective contributed to Western bias in the study of social movements. It played a significant role in internalizing the metaphor of “catching up,” which has been present implicitly or explicitly in most analyses on the movements of the region and which articulated expectations of the green movement based on the success story of the German Greens, for instance. The influence of the Danube movement, moreover, did not stop at the democratic changes around 1989. Even though scholarly interest in the Danube Circle focuses primarily on the late 1980s and early 1990s, the organization played an important role in the demonstrations against the Socialist government in 1998. According to the polls, these demonstrations changed voters’ preferences and contributed to the fall of the Socialist government. In spite of or, rather, together with these complex, sometimes contradictory phenomena and processes, the history of democratic changes in Hungary can hardly be discussed without mention of the role of the Danube movement.